When Ajibola Wasiu Opeyemi first planted cucumbers in 2013, he didn’t think far-ahead the farming system on which his farming success would be built a decade later. Fast-forward to now: his farm in Aboke village, Lagelu Local Government Area in Oyo State, is not only a demonstration plot but the heart of a Farmers’ Hub that exemplifies “circular farming”; where crop wastes, livestock, fish and soil all interlink in a loop of productivity, regeneration and profit. Ajibola puts it simply:

“I don’t want anything to be wasted on my farm, so all the waste I generate goes back to my animals and then to the soil.”

What is Circular Farming; and Why It Matters

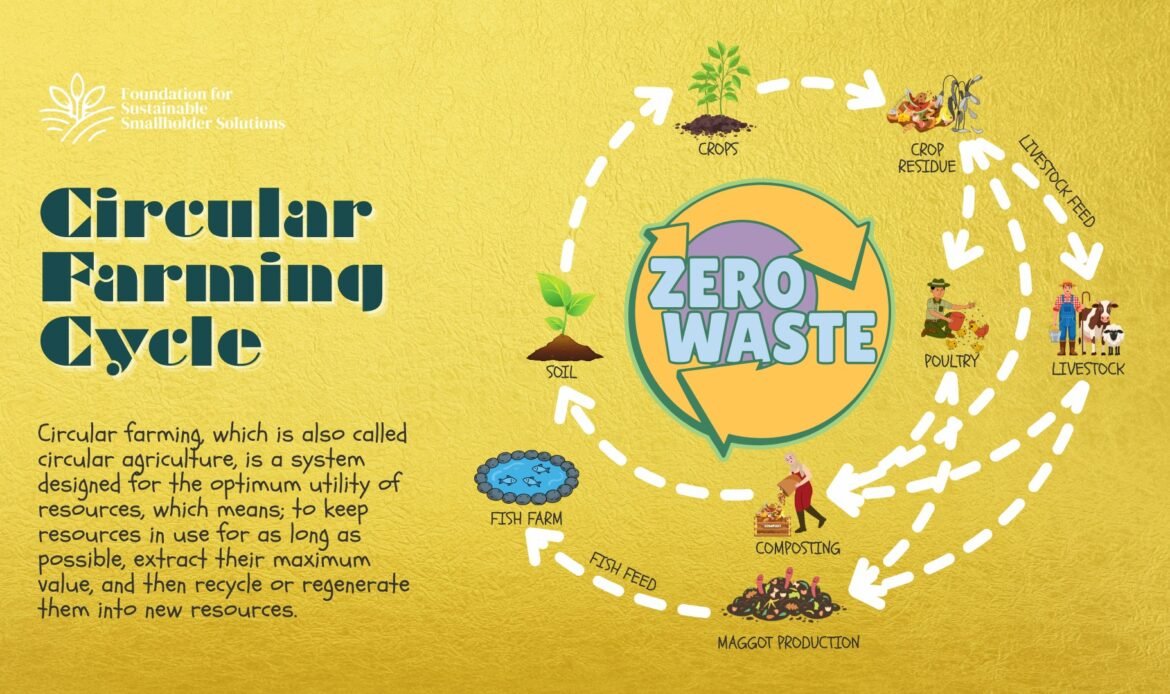

Circular farming, which is also called circular agriculture, is a system designed for the optimum utility of resources, which means; to keep resources in use for as long as possible, extract their maximum value, and then recycle or regenerate them into new resources. In farming terms, that means turning crop waste into animal feed, animal waste into compost, compost into soil fertility, and the cycle repeats.

Although circular farming is not yet a widespread concept in Nigeria, it is increasingly supported by research from across sub-Saharan Africa and other regions. A study published in Sustainability by MDPI in 2021 found that circular agriculture systems that integrate livestock, return crop residues to the soil, and recycle organic waste can substantially improve soil fertility, reduce reliance on external fertilisers, and increase farmers’ incomes.

In Nigeria, a 2022 study conducted among vegetable farmers in Cross River state and published by Integrity Research Journals revealed that most vegetable farmers recognise the benefits of regenerative agriculture, particularly in improving soil health and enhancing food security. However, many are hindered by high costs and insufficient access to training, which limits large-scale adoption.

More broadly, regenerative and circular agricultural practices such as composting, applying manure, integrating livestock, and minimal tillage are gaining ground across Africa. A report by the Africa Regenerative Agriculture Study Group highlights that these methods enhance resilience to climate shocks, reduce input costs, and improve long-term yields, offering a pathway to both environmental sustainability and rural prosperity.

For Nigeria, where many smallholder farmers contend with degraded soils, high input costs, climatic instability, and limited extension support, circular farming offers a practical solution. One that helps reduce farmers’ dependency on expensive synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, thereby lowering overall production costs and encouraging the use of organic alternatives. Over time, as posited by Tindwa et. al. (2024), the practice improves soil health and fertility, which in turn boosts yields and strengthens crop resilience to climate stress.

Lower input expenses also translate into better profitability and long-term sustainability for farmers, making circular farming a viable economic model rather than just an environmental ideal. Beyond farm economics, circular systems offer important ecological gains like improved nutrient cycling, reduced waste, and greater soil carbon storage; all of which contribute to a healthier and more resilient ecosystem.

Circular Farming in Practice through the Farmers’ Hub

Ajibola’s farm and the Farmers’ Hub he manages is a clear and practical demonstration of circular farming in action. After harvesting his sweetcorn, the remaining corn stover which includes the stalks and leaves often left to rot on fields is chopped and used to feed his livestock, including chickens, goats, and other animals. Their waste, instead of being discarded, is collected and carefully composted. The compost is then returned to the soil, enriching it and serving as an organic medium for raising seedlings in trays and cultivating new crops on the field.

In another utility loop within this system, Ajibola rears catfish in ponds and feeds them maggots produced from poultry waste. This process not only creates a natural protein source for fish feed but also eliminates the need for costly commercial feeds. Through these interconnected cycles, every by-product of one activity becomes the input for another, reducing waste and cutting operational costs.

His demonstration plots further illustrate the power of this approach. Seedlings are raised in nutrient-rich planting media, ensuring healthy plant growth and higher yields. Farmers visiting his hub witness these results first-hand, learning how simple, locally available resources can sustain a productive and profitable farm ecosystem.

Beyond his own fields, Ajibola’s hub provides access to verified agro-inputs, practical training on regenerative and circular practices, and regular field demonstrations. One such event organised with support from the Foundation once drew over 200 farmers eager to observe a successful sweetcorn trial, proof that the model works. These efforts cumulatively show that circular agriculture is far from an abstraction, it is a practical, replicable system that restores soil health, strengthens livelihoods, and offers a viable path towards sustainable food production in Nigeria.

A Case for Scaling the Idea and its Implications

The success of Ajibola’s hub suggests some lessons for broader adoption across Nigeria:

- Training and knowledge matter: Many farmers know the idea of regenerative/circular farming, but lack the training, resources or market access to implement it. The study in Cross River State found 81.3% of farmers cited financial constraints and 78% cited insufficient training.

- On-farm infrastructure counts: Composting areas, livestock integration, fish ponds, demonstration plots and input verification all cost time and effort. Ajibola’s hub had the support of the Foundation investment (~₦10 million) to build greenhouses, offices and stores.

- Demonstration and peer learning help adoption: The hub’s field day, demonstration plots and hands-on training enabled more than 1,000 local farmers per year to engage with circular farming practices.

- Looping waste into value streams reduces costs: By turning farm waste into feed or compost, Ajibola lowers his input costs and adds value. As Nigeria seeks to grow more food sustainably, circular loops become important.

- Policy and institutional support amplify impact: The Foundation and its partners support the establishment and creation of training programmes targeted at thousands of smallholders in regenerative agriculture approaches and show how institutional frameworks and support help.

Challenges and Considerations

Of course, circular farming is not a magic bullet. Some of the obstacles include:

- Up-front investment in infrastructure and training.

- Cultural and behavioural change: moving from “waste” mindset to “resource” mindset takes time and role models.

- Market and supply chain alignment: farmers need reliable inputs, good seeds, and channels for their produce.

- Monitoring and measurement: benefits accrue over time (soil health improves more slowly than a single harvest). Research suggests that increased soil organic matter and associated benefits may take years.

The Road Ahead

For Nigeria’s farming sector, which is critical to national food security, livelihoods and climate resilience, circular farming offers a promising pathway. The example set in Lagelu by Ajibola and his hub illustrates that with the right support, the right mindset and practical systems, waste can become profit, soil can regenerate and farmers can build more resilient livelihoods.

As Ajibola himself says: “When you value what you have, nothing goes to waste.” In a country where so much agricultural potential remains under-realised, closing the loop might just be one of the keys to unlocking it.

Reference

Africa Regenerative Agriculture Study Group (2021). Regenerative Agriculture: An opportunity for businesses and society to restore degraded land in Africa. 62pp.

El Janati, M., Akkal-Corfini, N., Bouaziz, A., Oukarroum, A., Robin, P., Sabri, A., Chikhaoui, M., & Thomas, Z. (2021). Benefits of Circular Agriculture for Cropping Systems and Soil Fertility in Oases. Sustainability, 13(9), 4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094713

Ovat, K. E., Ayi, N. A., Adesope, O. M., Idiku, F. O., & Osim, O. O. (2025). Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions: Understanding regenerative agriculture among vegetable farmers in Cross River State, Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Economics, 2(2), 13-25. https://doi.org/10.31248/JAERE2025.015

Tindwa, H. J., Semu, E. W., & Singh, B. R. (2024). Circular Regenerative Agricultural Practices in Africa: Techniques and Their Potential for Soil Restoration and Sustainable Food Production. Agronomy, 14(10), 2423. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14102423