As the effect of climate change worsens, crop yields in Africa could fall dramatically—one study projects an 18% drop in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) region yields by 2050 if current climate trends persist. At the same time, agriculture contributes roughly one-third of global greenhouse gases. Carbon farming offers a hopeful solution: by adopting practices that reduce atmospheric CO₂ levels, farmers can help cool the planet and boost their incomes.

In carbon farming, activities like planting trees, building soil health, and improving land management sequester carbon in biomass and soils. These “nature‑based solutions” can then be certified as carbon credits and sold on carbon markets, creating a new revenue stream for smallholder farmers. In short, carbon farming aligns ecological benefits with economic incentives—a synergy between climate goals and rural livelihood.

How Carbon Markets Work

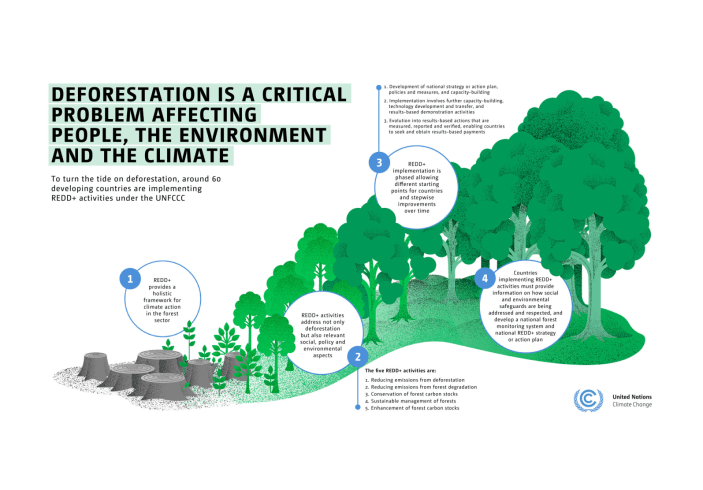

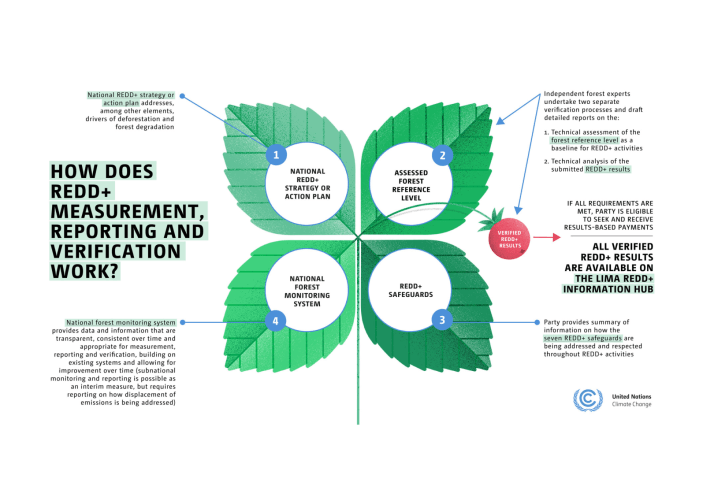

Carbon credits are tradeable certificates, each representing one ton of CO₂ (or equivalent) avoided or removed from the atmosphere. Governments and companies buy credits to compensate for their emissions. There are two main types of carbon markets:

- Compliance markets (e.g. the EU Emissions Trading System) mandate emission limits. Credits here often come from forest protection (REDD+) or large industrial projects, but strict rules historically excluded most soil and farm practices.

- Voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) allow any organisation to offset emissions by buying credits. In recent years VCMs have opened the door to agricultural credits and innovative methods. Unlike compliance markets, voluntary schemes can certify credits for soil carbon and regenerative practice.

In a voluntary market project, farmers adopt carbon-smart practices and measure the emissions reduced or carbon sequestered. An approved carbon standard (like Verra’s VCS or the Gold Standard) verifies the gains—an expensive process of field surveys and monitoring. Once verified, the project issues credits (usually through registries) that buyers can purchase. The buyer may be a global company seeking to offset emissions, or a fund investing in climate action. Thus, farmers get paid when large emitters buy their carbon credits.

Global demand for carbon credit is growing rapidly. Voluntary carbon credits are currently valued globally at roughly $2 billion per year, with forecasts of 5–50× growth by 2030. This could unlock significant climate finance for Africa. Today, Africa accounts for only ~16% of the world’s traded credits, meaning a huge untapped market. For Nigeria’s smallholder farmers, this represents both opportunity and challenge: with the right support, they could join global VCMs and earn income from carbon sequestration.

Carbon Farming Practices for Smallholders

Carbon farming isn’t a single technique, but a suite of soil- and tree-based practices. In Nigeria and the SSA region, promising methods include:

- Agroforestry: Planting trees (fruit trees, nitrogen-fixing species, etc.) among crops or around fields. Trees absorb CO₂ as they grow, storing carbon in wood and roots. They also shade crops, reduce erosion, and eventually produce fruit or timber. This has been a flagship strategy in African projects.

- Conservation Tillage / No-till: Reducing ploughing and soil disturbance keeps more carbon locked in the soil and prevents erosion. Farmers leave crop residues on the field, which decompose into humus.

- Cover Crops: Growing crops (often legumes) in off-season or between rows. Cover crops add biomass and nitrogen to the soil, boosting organic matter and carbon content. They also suppress weeds and improve moisture retention.

- Organic Amendments (Manure, Compost): Applying compost or animal manure enriches soil organic carbon and nutrients. Studies show that adding organic matter can significantly enhance soil carbon stocks over time.

- Crop Rotation & Intercropping: Rotating different crops (including deep-rooting plants) or planting multiple crops together enhances nutrient cycling and soil structure, indirectly supporting carbon build-up.

These climate-smart practices improve soil health and productivity while sequestering CO₂. For example, a leguminous cover crop like cowpea fixes atmospheric nitrogen and leaves biomass that becomes soil carbon. An agroforestry project in Kenya found that combining fruit trees with maize increased yields and stored roughly one ton of carbon per 0.6 hectares per year (see Farm Africa case study below).

Voluntary Carbon Market Trends (2024–2025)

The voluntary carbon market has been volatile but shows strong underlying demand.

Key trends include:

- Market Size and Growth: The global VCM was valued around $2 billion in 2024, with hundreds of millions of credits issued. Africa’s share of issued credits has roughly doubled (from ~13.5% in 2018 to ~25% by 2023), indicating rising interest. However, the overall market dipped in 2023—Ecosystem Marketplace reports VCM value fell to ~$723 million (a 61% drop from 2022) due to quality concerns. Within this, agriculturally-related credits did see a 24% volume rise, but at lower prices.

- Credit Types: Worldwide, most credits are still from avoided emissions (forest protection, renewable energy), not removals. In Africa ~50% of credits come from forestry/land projects (mostly conservation), with ~42% from community projects (e.g. cook-stoves, water). Pure carbon removals (soil, technology) contribute an inconsequential share. However, demand for high-integrity nature-based removals is growing, often at price premiums (see below).

- Credit Prices: Prices vary hugely by project type. Nature-based avoidance credits often trade at only a few dollars per ton. For example, Shell paid an average of ~$4.15/ton for its 2024 credits. By contrast, engineered removals (like BECCS bioenergy credits) fetch a far higher price. Notably, Microsoft’s 2024 purchases averaged about $189/ton, reflecting its focus on cutting-edge removals. Bear in mind Microsoft’s portfolio was BECCS-heavy; Shell’s were mostly low-cost forestry and renewables. Generally, high-quality or socially‑beneficial credits command premiums—small-farm projects with co‑benefits often sell above baseline prices.

- Major Buyers: The largest corporate buyers in 2024 were in the energy and finance sectors. For instance, Shell (oil and gas) retired ~14.5 million credits in 2024, and financial companies also feature prominently. The tech industry (Microsoft, Google, Meta) credit retirement rate is increasingly growing, often at higher prices (e.g. Microsoft’s $189/ton). Together, the financial and energy sectors lead voluntary offsets globally. However, buyer preferences are shifting toward durable removals, long-term offtake deals, and projects with clear co-benefits.

Examples of Carbon-Farming Projects

Across Africa, several pilot programs are demonstrating that smallholder carbon farming can work:

- Farm Africa – “Growing Green” (Eastern Kenya): Starting in 2020, Farm Africa partnered with Rabobank’s Acorn platform and AGRA to engage 21,500 smallholder farmers in Embu and Tharaka Nithi counties. Farmers planted fruit and nitrogen-fixing trees on formerly degraded lands (14,175 ha in total). By late 2023 they had sequestered ~24,945 tonnes CO₂ (creating the same number of “Carbon Removal Units”). Significantly, 80% of the revenue from selling those credits goes directly to the farmers. The farmers have used the income for school fees, farm expansion, and new businesses. This agroforestry project boosted yields (30–50% higher in trial plots) and improved soils health while linking villagers to international carbon buyers.

- Tourba Carbon Initiative (Nigeria): Tourba is an agritech startup that launched carbon farming programs in Nigeria in 2024. Its pilots in Niger and Nasarawa states covered over 15,000 hectares by intercropping crops with agroforestry. Tourba’s staff trains farmers for 18 months and helps prepare them for carbon certification. The company aims for 1 million hectares of smallholder participation by 2030. At our recent webinar commemorating the World Earth Day 2025, Tourba’s Emmanuel Orjichukwu highlighted that carbon farming “directly improves soil health, enhances yields, and gives farmers an additional source of income through the sale of carbon credits”. They have already extended the model to Kano, Kaduna, Bauchi and plan to hire dozens of local extension workers to support farmers.

- Rabobank Acorn Agroforestry Programme (Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia): Supported by FSD Africa, this initiative provides “carbon loans” to smallholders to invest in agroforestry. In 2023, it began disbursing funds and training in Nigeria (and neighbouring countries). Farmers use the loans to buy tree seedlings and plant them alongside cash crops. The extra income from eventual carbon credit sales is designed to make the transition affordable. Early progress reports note that farmers have started planting trees and expect higher crop yields. (The first carbon trades are planned in ~3 years, after trees mature and can be measured.)

- Zowasel Sorghum Project (Nigeria): In a partnership with IDH and Diageo’s Guinness, Zowasel is helping 2,000 sorghum farmers in Southwest Nigeria adopt regenerative techniques. A key innovation is its digital MRV platform called D-MRV, which uses satellite data, mobile apps and on-the-ground verification to measure how much carbon is sequestered. This assures buyers of the credibility of the credits. Zowasel also provides its ACESS credit-scoring tool so farmers can get financing for inputs while they transition. These tech-driven programs are explicitly designed to link smallholders to the global voluntary market, guaranteeing them a market for produce and, potentially, carbon payments.

Together, these examples show that both NGO-led and private-sector models can enrol farmers in carbon farming. In each case, support structures (training, financing, aggregation) are crucial, as is a clear connection between farmer actions and market payment.

Challenges for Smallholder Participation

Despite the promise, smallholders face real barriers in carbon markets, Emmanuel Orjichukwu at our recent webinar highlighted the following:

- High upfront and transaction costs. Changing practices (buying seedlings, managing new systems) requires capital. Critically, monitoring and verification are expensive. Independent auditors must certify each credit, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars—often prohibitive for small projects. Without aggregation, individual farms can’t afford verification fees.

- Complexity and standards. Carbon projects require detailed record-keeping (baselines, activity data) and adherence to strict rules. These “one-size-fits-all” standards can exclude marginal farmers. As one expert put it, strict credit requirements, limited financial resources, and weak governance frameworks hinder smallholders. Many farmers simply lack the know-how or paperwork to enrol on their own.

- Market uncertainty. Farmers must often sign multi-year contracts before knowing if buyers will materialise. Voluntary buyers’ pledges are long-term and sometimes vague, creating a perceived risk for farmers. There is also uncertainty about future carbon prices. Since adopting new techniques costs money, farmers need the credit price to be high enough to cover these costs plus a risk buffer. If prices fall (as they did around 2023) or if too few credits are bought, smallholders may not earn enough.

- Fragmented supply. In Nigeria and much of SSA, millions of small farms are scattered. Creating a project often requires grouping them into cooperatives or using an intermediary. Without good aggregation mechanisms, many farmers can’t participate.

- Awareness and capacity. Many farmers and even local NGOs are simply unaware of carbon markets. There is limited technical assistance in rural areas. Farmers may be sceptical or prefer immediate income crops over unseen future carbon payments.

These hurdles mean that donor and NGO support is often needed just to get projects off the ground. Without grant or concessional funding to cover early costs, few farmers can join carbon programs.

Recommendations: How to Make It Work

To unlock carbon finance for smallholders, coordinated action is required:

- Build farmer capacity: NGOs and extension services should train farmers in carbon-friendly techniques (agroforestry, cover crops, etc.) and in basic record-keeping. Field schools or workshops can demonstrate benefits. Encouragingly, when farmers see healthier soils and higher yields (as in the Farm Africa project), they become champions of the approach.

- Aggregate and simplify: Help smallholders form groups or cooperatives that can collectively register for carbon projects. Standardised, programmatic approaches (approved smallholder methodologies) can reduce individual paperwork. For example, using mobile apps or simple survey protocols allows thousands of farmers to be measured together. Donors can subsidise MRV costs, or support tech tools (like satellites or drones) that monitor large areas cheaply. Platforms like Zowasel’s D-MRV show how digital solutions can cut costs.

- Secure fair compensation: Corporations and carbon buyers should commit to purchasing credit volumes upfront (giving farmers price guarantees). Funders could offer “floor prices” for carbon credits in early projects to insure farmers against market swings. In Nigeria, for instance, keeping prices in the range of $15–25 per ton may be necessary to make agroforestry viable. Buyers (or donor-backed funds) can also provide bridging finance to farmers while credits are verified and sold.

- Leverage co-benefits: To attract more support, carbon projects should emphasise wins beyond climate. Credits that also improve food security, biodiversity, or gender equity tend to fetch price premiums. For example, training women in agroforestry was a plus in Kenya (Farm Africa noted rising women’s leadership in these projects). Policymakers are urged to prioritise carbon programs that explicitly deliver economic and nutrition benefits. This can unlock additional development funding (not just climate finance) and help justify national incentives.

- Strengthen policies and partnerships: Governments should include agricultural soils and forests in their climate targets (NDCs) and create favourable regulations. For instance, Nigeria or regional bodies could streamline land-tenure rules or offer tax breaks for carbon farming. Multilateral initiatives like the African Carbon Markets Initiative (ACMI) recommend building market integrity and clear rules. Donors and international agencies can help by providing grants or blended financing to pioneer projects and by encouraging corporations to set transparent carbon purchasing plans.

By addressing barriers and investing in NGOs like ours providing outreach, technology, and fair deals, stakeholders can ensure smallholders see real value in carbon farming. This means turning farmers into providers of climate solutions. As one analysis notes, carbon markets should not be “one-size-fits-all”—they must be designed with small farmers’ needs in mind.

In conclusion, carbon farming in Nigeria and SSA offers a win-win: it helps mitigate climate change and bolsters farm resilience. When trees grow on the farm or soils are enriched, carbon finance makes them “worth more in the ground than being cut down”. With the right support, for foundations like us, Nigerian—and by large African—smallholders can seize this opportunity—earning income from carbon credits while building a better livelihood and healthier, more productive farms.

References

- Supporting Climate-Resilient African Smallholder Farmers Through Carbon Markets – SAIIA

- Carbon Farming: Definition & Opportunities – Welthungerhilfe

- Africa’s green wealth: unlocking the potential of carbon markets | UNREDD Programme

- Agroforestry and carbon markets transform farming in eastern Kenya – Farm Africa

- Introduction to the Voluntary Carbon Market in Africa

- Shell and Microsoft Are The Biggest Carbon Credit Buyers in 2024: What Projects Do They Support?

- Behind the green curtain: big oil and the voluntary carbon market – Carbon Market Watch

- Tourba Sensitises Kaduna Farmers on Carbon Farming – THISDAYLIVE

- Rabobank Acorn Agroforestry Carbon Programme – FSD Africa

- IDH and Zowasel Form Partnership to Transform Nigeria’s Sorghum Value Chain through Regenerative Agriculture – AgriBusiness Global

- Overcoming Barriers to the Development of an Agricultural Carbon Market – Farm Foundation